- Home

- Artists/Poets

- Adonis

Adonis

Born in 1930 in a small village in Syria, poet, artist, essayist, translator, and perennial favorite for the Nobel Prize, ADONIS (Nee Ali Ahmad Said Esber) is considered the “Greatest Living Poet of the Arab World.”

ADONIS (Nee Ali Ahmad Said Esber)

1930 - Present

Born in 1930 in a small village in Syria, poet, artist, essayist, translator, and perennial favorite for the Nobel Prize, ADONIS (Nee Ali Ahmad Said Esber) is considered the “Greatest Living Poet of the Arab World.” He led a modernist movement in the second half of the 20th century. In terms of innovation “exerting a seismic influence on Arabic poetry comparable to T.S. Eliot’s in the western world than any other contemporary Arab poet.

For Adonis, poetry is a vision (ru’ya) a “leap outside of established concepts, a change in the order of things and in the way we look at them.” His work often centers not only on the process of poetic creations but a visual narrative resulting from the depth of his imagery –imagined and realized. For decades, Adonis has been a controversial poet, promoting unsettling ideas about poetry, politics, religion, tradition and modernity, in an effort to keep the Arabic legacy alive through constant reexamination of its tenets.

POETRY IN SIGHT

Adonis is not a poet: he is not one poet amongst others, but the poet, the only one. His poems have changed what poetry could be in the Arabic language, and in any language. A master at the humblest, most serene and metaphysical poetry, he has equally invented new ways of practicing these archaic, ambitious forms: the epic, didactic poetry. A heroic figure in a time that does not favor them, he still is, at nearly ninety, the boldest young man one could meet, who has long championed a more free, more active, more humane way of being human.

His life as a poet makes him more than a writer: he is a voice. When Adonis speaks, the rest of the world stays silent to hear his word, to feel, and to think. And more than a voice, he is a man of his craft, an artist, a maker – the Greek word poietes signifies nothing but that. He has worked on every word of his language, and he has looked at every piece of stone, every flower, every line on a face that has ever made the world.

Poets are sometimes thought to be abstract creatures, living in an ether of fantasies and ideas. Adonis is the living evidence that poets are no such beings: he has, in his mouth, the taste of the rose, of water, of soil. These are no abstractions to him, quite the contrary: he will know the specificity of every object that is not an item, but a pure, irreducible singularity. The word is the world. A word, a letter, contains a light at once new and ancestral every time it is uttered. Such are the things: they are new every time they are brought to our consideration, and yet they carry within themselves all the things that have ever been, of the same species or of another.

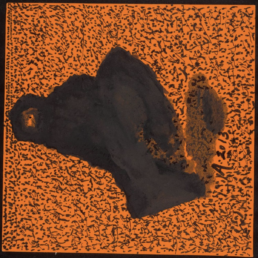

The body of visual work Adonis initiated in the mid-1990s, and that is still on going to this date, is a monument of words and things, modest and sublime. The very first ones could be compared to Joseph Cornell’s boxes: they were recipients for little stones, pieces of wood, found objects, left-over bits of metal. Adonis gathered them, gave them a form – often a human one, willingly or unwillingly -and added poetry – poems that were part of his own museum of poetry. As the series expanded, forms started to appear, shaped with ink or gouache. The loose gesture with which liquid inhabited the paper is the closest to a direct manifestation of the poet’s inspiration in a poem. The words are sent to the world, as the ink is sent to the paper.

One can certainly trace back this practice to Victor Hugo’s drawings, and even more, to the Surrealists – it is a well-known fact that their ideology of opening-up human sensitivity through poetry has exerted a considerable impact on Adonis. One can think of Sufism, and the loss of oneself in a poetic, transcending ecstasy. All references would be relevant, but none completely. With his rhakimas, his paintings-collages-drawings-ma

What is the status of these objects? The question is irrelevant. It would be as irrelevant as to ask: what is poetry?, hoping for a definite answer. Poetry is the question whose answer lies in being asked, and for which no actual answer can ever be given. Each of those works calls upon us to be more poetic, more open, more alive. They have tragedy embedded in them, and the figures unwillingly invoked on Adonis’ drawings seems to invite us to join them in a sublime dance of the senses and of the mind.

What are they? They are radical poems, they are creations of a free mind, offering us his free mind, digging with his bare hands in all the fields that have ever existed and will ever exist, sensing the earth, holding the roots of the tree of life and letting all the world’s creatures wander through his fingers, dead or alive, both at the same time. Each of those works is an heroic manifestation of all it is poets see, and give us to see, beyond cultures and ages, beyond lives, in a place where worlds and words are finally reconciled.

Donatien Grau